A Comprehensive Report on Diseases in Cattle and Dairy Cows: Causes, Prevention, and Treatment

Table of Contents

Part I: Fundamentals of Herd Health Management

1. Introduction: The Strategic Importance of Disease Control

The health of a cattle herd, especially dairy cows, is the cornerstone of a successful and sustainable livestock industry. Effective control of diseases in cattle is not merely a technical requirement but a decisive economic strategy. The impact of disease extends far beyond immediately visible losses like mortality. They cause severe “hidden” economic losses, including reduced milk production, decreased weight gain, impaired fertility, increased costs for medication and treatment, and the creation of barriers to transportation and trade. Agricultural statistics indicate alarming prevalence rates for common diseases in Vietnam, with helminthiasis affecting 30-50% of herds, hemorrhagic septicemia 10-20%, and mastitis 10-15%, demonstrating the persistent economic burden faced by farmers.

In this context, biosecurity emerges as the first, most effective, and most economical line of defense. Biosecurity is not just about cleaning barns; it is a system of scientifically designed and synchronously implemented management practices aimed at preventing pathogens from entering the farm and controlling their spread within the herd. Key components of a comprehensive biosecurity program include:

- Access Control: Minimize the entry and exit of non-essential people and vehicles. Disinfectant footbaths or wheel dips must be mandatory at all entry points to the farming area to neutralize pathogens that may adhere to wheels or footwear.

- Breeding Stock Management: The source of breeding animals must have a clear history. Newly imported cattle must be quarantined in a separate area for at least one month to monitor for signs of disease. During this period, testing for dangerous infectious diseases, especially Tuberculosis, should be conducted before they are allowed to join the herd.

- Cleaning and Disinfection: Perform daily mechanical cleaning (sweeping, scrubbing) of barns, feed troughs, water troughs, and equipment. Subsequently, conduct regular disinfectant spraying with suitable chemicals like lime powder, formalin, or iodine compounds to eliminate pathogens in the environment.

- Vector Control: Flies, mosquitoes, ticks, and mites are not just nuisances; they are vectors for many dangerous diseases such as Lumpy Skin Disease and bloodborne parasites. Controlling them through insecticide spraying, clearing bushes, and maintaining drainage is an indispensable part of biosecurity.

- Waste Management: Manure and other farm waste are rich sources of pathogens and parasite eggs. They should be collected daily and treated using composting (thermal treatment) to effectively kill pathogens before being used as fertilizer or released into the environment.

2. Classification and Diagnostic Approach for Major Disease Groups

For effective management and control strategies, diseases in cattle can be classified into major groups, each requiring a different approach:

- Infectious Diseases: Characterized by rapid and strong transmission, with the potential to cause major outbreaks and widespread damage. This group requires community-level interventions such as mandatory vaccination, epidemiological surveillance, and official outbreak declarations when necessary.

- Parasitic Diseases: These are often chronic, not causing mass deaths but gradually weakening livestock, leading to silent economic losses through reduced weight gain, lower milk yield, and decreased immunity.

- Metabolic & Internal Medicine Diseases: This group is non-infectious, typically arising from imbalances in nutritional management and care, and is particularly common and severe in high-producing dairy cows due to high production stress.

- Reproductive Diseases: Includes issues related to the reproductive process and the postpartum period, directly affecting breeding capabilities and the milk production cycle, which are key determinants of a dairy farm’s profitability.

The link between environmental factors, management, and disease outbreaks is very clear. Factors like sudden weather changes (seasonal transitions, rain, humidity) are often recorded as triggers for diseases such as Hemorrhagic Septicemia, Diarrhea, and Ruminal Bloat. This indicates a causal chain: environmental changes cause stress in animals, leading to a weakened immune system. Consequently, opportunistic pathogens, which may already reside in the animal’s body (e.g., Pasteurella multocida in the upper respiratory tract), can multiply and cause clinical disease. Therefore, effective prevention measures must go beyond vaccination to include improving the microclimate of the barn, providing adequate nutrition, and minimizing stress factors.

Furthermore, epidemiological reports from the Department of Animal Health show the continuous circulation of dangerous diseases like Foot-and-Mouth Disease (FMD) and Lumpy Skin Disease. This emphasizes that no farm can exist in isolation. The health of one herd is closely dependent on the epidemiological situation of the entire region. The transport and trade of livestock without quarantine is the fastest and most dangerous route for spreading diseases between localities. Thus, adhering to animal quarantine regulations becomes one of the most critical biosecurity measures, sometimes even more important than the internal hygiene practices of the farm itself.

Part II: Dangerous and High-Impact Infectious Diseases

1. Foot-and-Mouth Disease (FMD)

Foot-and-Mouth Disease (FMD) is listed by the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) as one of the most dangerous infectious diseases for livestock, causing enormous economic losses and serving as a barrier to international trade.

Etiology and Epidemiology

The disease is caused by a virus from the Picornaviridae family. This virus is highly variable, with seven known major serotypes: A, O, C, Asia1, SAT1, SAT2, and SAT3. In Vietnam, epidemiological studies have identified the circulation of three main types: O, A, and Asia1.

This is an acute infectious disease with an extremely rapid and strong transmission rate. The virus can be transmitted through multiple routes: direct contact between sick and healthy cattle; indirect contact through contaminated feed, water, air, or equipment. Notably, the virus can persist in droplets and be spread by wind for several kilometers, making containment efforts very difficult. A dangerous epidemiological feature of FMD is that cattle, after recovering from clinical symptoms, can continue to carry the virus and shed it into the environment for a very long time, up to 2-3 years, becoming a latent and hard-to-control source of infection.

Clinical Signs and Lesions

After an incubation period of 2-7 days, cattle begin to show clear clinical signs.

The first symptom is usually a sudden high fever, up to $40-41^\circ C$, accompanied by depression, loss of appetite, and lethargy.

The most characteristic and typical sign is the appearance of vesicles (blisters) filled with clear fluid. These vesicles commonly appear on thin-skinned areas and mucous membranes such as the mouth (tongue, gums, lips), muzzle, coronary band, interdigital space, and teats.

After about 1-3 days, these vesicles rupture, leaving shallow, red erosions that cause intense pain. The oral lesions lead to excessive, foamy, stringy salivation. The foot lesions make walking very difficult, causing lameness; cattle often stand with their feet drawn up or lie down, a posture farmers describe as “rice pounding.” Affected dairy cows experience a sudden drop in milk production.

The disease can lead to dangerous complications such as secondary bacterial infections of the lesions, pneumonia, mastitis, and abortion. In young calves, the virus can attack the heart muscle, causing acute myocarditis and sudden death, often without clear vesicular lesions.

Prevention Measures

Vaccination is considered the most proactive and effective prevention method. As immunity lasts for about 6 months, routine vaccination of the entire herd twice a year is necessary. Calves can receive their first shot at 2-4 months of age, depending on the vaccine type and maternal antibody levels.

During an outbreak, ring vaccination of healthy herds in the threatened zone is an urgent measure to halt the spread.

Alongside vaccination, strict biosecurity measures are mandatory: complete isolation of sick animals, a ban on livestock movement and grazing in the affected area, and thorough cleaning and disinfection of barns and the environment with lime powder or effective chemical disinfectants.

Treatment Methods

As FMD is a viral disease, there is no specific cure. Interventions primarily focus on symptomatic treatment, preventing secondary infections, and boosting the animal’s resistance.

- Local Care: Clean the lesions on the mouth, feet, and teats daily with mild antiseptic solutions like saline, 1% potassium permanganate, or methylene blue. Some folk remedies using mildly acidic liquids like lemon or starfruit juice to wash the lesions can also help dry the wounds and reduce pain.

- Control of Secondary Infections: Use antibiotics (topical powders like Penicillin, Sulfonamide, or systemic injections) to prevent bacteria from invading the lesions and causing more severe infections.

- Supportive Therapy: Administer supportive drugs like Vitamin C, B-complex vitamins, and Caffeine to boost the animal’s immunity. Provide soft, easily swallowed food (gruel, finely chopped young grass) and sufficient clean drinking water to aid recovery.

In cases of an outbreak caused by a new viral serotype or in small, localized outbreaks, veterinary authorities may implement a stamping-out policy, culling all infected livestock to quickly and completely eradicate the disease source.

The existence of multiple FMD virus serotypes and subtypes is the greatest challenge in prevention and control. A vaccine can only provide protective immunity against the viral types it contains. This means a vaccinated herd can still get sick if exposed to a new or different serotype not included in the vaccine. This logic implies that prevention cannot solely rely on the farmer’s decision. It requires a proactive national epidemiological surveillance system to continuously identify circulating virus types and recommend the most suitable polyvalent vaccine for each region and time. Furthermore, the role of carrier animals after recovery is extremely dangerous. They become epidemiological “time bombs,” showing no symptoms but continuously shedding the virus. This indicates that disease control cannot focus only on treating clinically ill animals but must also include strict management and monitoring of recovered ones, and rigorous quarantine for trade and transport to prevent them from becoming sources of infection.

2. Hemorrhagic Septicemia

Hemorrhagic Septicemia is an acute infectious disease, often with high mortality, especially in regions with adverse farming conditions and climate.

Etiology and Epidemiology

The causative agent is the bacterium Pasteurella multocida. This bacterium is quite resilient and can survive in moist, dark soil and barns for 1-3 months.

A key epidemiological feature is that P. multocida often exists as a harmless commensal on the upper respiratory tract mucosa of healthy cattle. The disease only breaks out when the animal’s resistance is lowered by stress factors. These factors include sudden weather changes (especially during the rainy season, from June to September), long-distance transport, changes in diet, or overwork.

The disease is primarily transmitted via the respiratory route when cattle inhale the pathogen from the air, or via the digestive route by consuming food or water contaminated with secretions from sick animals. Blood-sucking insects can also act as mechanical vectors.

Clinical Signs and Lesions

Hemorrhagic Septicemia can manifest in three main forms of varying severity:

- Peracute (Fulminant) Form: The disease progresses extremely rapidly. Cattle can die suddenly within 24 hours with few clear symptoms. In some cases, animals exhibit very high fever ($41-42^\circ C$) and neurological signs such as aggression, frenzy, and head-pressing before death.

- Acute Form: This is the most common form, with an incubation period of 1-3 days. Cattle suddenly develop a high fever ($40-42^\circ C$), become lethargic, depressed, lose their appetite, and stop ruminating. Respiratory signs are very typical: rapid, difficult, and labored breathing, with profuse nasal and salivary discharge. The characteristic sign is a hot, hard, painful swelling in the throat, brisket, and neck region due to edema and subcutaneous hemorrhage, which compresses the airway. Some cases may show digestive disturbances like diarrhea, possibly with blood. Without prompt treatment, the mortality rate in this form is very high, up to 90-100%.

- Chronic Form: Cattle that survive the acute form may transition to this state. Symptoms persist for several weeks, including arthritis (causing difficulty walking and lameness) and chronic pneumonia/bronchitis (causing a persistent cough). The animal typically becomes progressively emaciated and dies from exhaustion.

Prevention Measures

Vaccination is the most proactive, effective, and economical prevention measure. Routine vaccination should be done every 6 months, typically before seasonal changes (e.g., before the rainy season) to provide the best immunity for the herd.

Additionally, applying good management and care practices to enhance the natural resistance of cattle is crucial. This includes providing adequate nutrition and clean drinking water, keeping barns dry and well-ventilated, and avoiding overworking or stressing the animals. Regular cleaning and disinfection of barns also help reduce the pathogen load in the environment.

Treatment Methods

As a bacterial disease, Hemorrhagic Septicemia can be treated effectively with antibiotics, especially if detected and treated early.

- Antibiotic Use: Highly effective antibiotics include Streptomycin, Kanamycin, Penicillin, Oxytetracycline, and Gentamycin. It is crucial to strictly follow the dosage instructions from the manufacturer or veterinarian and to complete the full treatment course of 4-5 days to prevent drug resistance and relapse.

- Supportive Therapy: Antibiotic treatment should be combined with supportive measures to help the animal overcome the critical phase. These include antipyretics (e.g., Analgin), supportive and cardiac stimulants (Caffeine, Vitamin B1, Vitamin C), and fluid therapy (saline, glucose) for severely weakened and dehydrated animals.

- Nursing Care: Sick animals must be immediately isolated to prevent spreading the disease. They should be cared for in a quiet, clean environment with adequate food and water to support recovery.

Unlike infectious diseases that invade from the outside like FMD, Hemorrhagic Septicemia can be considered an “endogenous” or “opportunistic” disease. The pathogen P. multocida often already exists within the herd, colonizing the respiratory tracts of healthy animals. The disease only erupts when the host’s immune barrier is breached by stress factors. This means that even with full vaccination, if management, care, and nutrition are poor and cattle are stressed, an outbreak can still occur. Vaccination significantly reduces the severity of the disease and mortality, but good management is the key factor in preventing the initial outbreak. Furthermore, because the acute and peracute forms progress so rapidly, the difference between saving and losing a cow depends entirely on early detection and antibiotic intervention within the first few hours. Therefore, daily observation of the herd to recognize the earliest abnormal signs (like loss of appetite, slight fever) is an essential management skill.

3. Lumpy Skin Disease (LSD)

This is a newly emerging infectious disease in Vietnam in recent years, causing significant economic losses due to its impact on productivity and trade.

Etiology and Epidemiology

The disease is caused by a virus from the Poxviridae family, genus Capripoxvirus, the same genus as the viruses causing sheep pox and goat pox. It is important to emphasize that the LSD virus is not infectious and does not cause disease in humans.

The primary and most effective mode of transmission is through blood-sucking insects such as flies, mosquitoes, ticks, and mites. The disease can also be transmitted through direct contact between animals, or indirectly through shared feeding troughs, water troughs, equipment, or contaminated needles. The virus is also found in milk, semen, and can be transmitted transplacentally.

The LSD virus is highly resistant and can survive for long periods in the environment. It can remain viable in dry skin scabs shed from nodules for up to 35 days and persist in dark, damp barns for months, complicating disinfection efforts.

Clinical Signs

After an incubation period of 4 to 14 days, cattle begin to show clinical signs.

The disease usually starts with a high fever, possibly over $41^\circ C$, loss of appetite, weakness, and a marked decrease in milk production in lactating cows.

The most characteristic and easily recognizable symptom is the formation of firm, round, raised skin nodules, 2-5 cm in diameter. These nodules appear all over the body but are concentrated on the head, neck, limbs, udder, genitals, and perineum.

These nodules may later become necrotic in the center, ulcerate, and leave permanent pitted scars on the skin upon healing, reducing the value of the hide.

Other symptoms may include swelling of superficial lymph nodes (prescapular, prefemoral) and edema in dependent parts of the body like the legs, brisket, and dewlap. The disease can cause serious reproductive complications such as temporary or permanent infertility in bulls and abortion in pregnant cows.

Although the mortality rate is generally low (1-5%), the morbidity rate can be high (10-20%), and economic losses mainly stem from reduced productivity, treatment costs, and trade restrictions.

Prevention Measures

Vaccination is the most proactive and effective prevention measure currently available. Live attenuated vaccines like Lumpyvac (Turkey) or Mevac LSD (Egypt) are licensed and widely used, providing good protection. The vaccine can be administered to calves from 2 months of age, and immunity typically lasts for 12 months.

Since the main transmission route is through insects, controlling and eliminating disease vectors is an indispensable pillar of the prevention strategy. It is necessary to regularly spray insecticides against flies, mosquitoes, and ticks on the cattle and in the surrounding environment; clean barns, clear bushes, and eliminate stagnant water to reduce insect breeding sites.

General biosecurity measures such as isolating sick animals, and cleaning and disinfecting barns should also be strictly applied.

Treatment Methods

Similar to other viral diseases, there is no specific cure for Lumpy Skin Disease. Treatment focuses on alleviating symptoms and preventing secondary infections.

- Symptomatic Treatment: Use antipyretics like Efferalgan, Analgin, or Paracetamol to control the high fever.

- Control of Secondary Infections: Administer broad-spectrum antibiotics (e.g., Cefquinome, Oxytetracycline) via injection to prevent secondary bacterial infections in the skin lesions and other internal organs.

- Boosting Immunity: Supplement with vitamins (A, D, E, B-complex), electrolytes, and liver tonics to support the immune system and help the cattle recover faster.

- Local Care: Clean and disinfect the skin lesions with appropriate solutions to prevent infection and promote healing.

Due to LSD’s primary transmission mechanism via insect vectors, an effective prevention strategy requires a dual approach: building active immunity in the herd through vaccination while simultaneously breaking the transmission chain by strictly controlling the population of blood-sucking insects. Vaccinating without controlling flies, mosquitoes, and ticks will be insufficient, as cattle can still be bitten and infected while waiting for the vaccine to take effect. This is an integrated prevention strategy that demands a combination of medical intervention and environmental management. Although the mortality rate is low, the economic impact of LSD is significant and prolonged. The nodules not only reduce hide value but also cause pain and affect the animal’s overall health. The reduction in milk yield, abortions, and infertility cause severe and long-term losses to production and herd development, far exceeding the losses from mortality alone.

4. Bovine Tuberculosis

Bovine Tuberculosis is a dangerous chronic infectious disease that not only causes economic losses to the livestock industry but also poses a serious threat to public health.

Etiology and Epidemiology

The disease is caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium bovis, an acid-fast bacillus that is highly resistant in the environment.

A particularly dangerous aspect of Bovine Tuberculosis is its ability to be transmitted to humans (a zoonotic disease). Humans can become infected by drinking unpasteurized raw milk from sick cows, or through close contact by inhaling air containing pathogens coughed up by the cows.

Transmission among cattle in a herd occurs mainly through two routes: respiratory (most common) and digestive. Healthy cattle can inhale bacteria shed into the air by sick animals or ingest contaminated feed, water, or milk.

Clinical Signs

Tuberculosis has a silent and chronic progression, so early-stage symptoms are often unclear and difficult to detect.

- Pulmonary Form: This is the most common form. Cattle show progressive emaciation, weakness, and a chronic dry cough, often in fits, especially at night or during exercise. Later, breathing becomes difficult, and they may cough up phlegm mixed with pus or blood.

- Gastrointestinal Form: Cattle suffer from persistent diarrhea with a foul odor, which does not respond to common anti-diarrheal medications.

- Mammary Form (Tuberculous Mastitis): Often seen in dairy cows. One or more quarters of the udder become enlarged and firm but are not hot or painful. The supramammary lymph nodes also become enlarged and hard. Milk production gradually decreases, and the milk can contain large numbers of tubercle bacilli, serving as a direct source of infection for humans and calves.

- Lymph Node Form: Superficial lymph nodes such as the submandibular and prescapular nodes become enlarged, hard, non-mobile, and are not painful upon palpation.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis based on clinical signs is very difficult due to the non-specific and chronic nature of the disease. Therefore, specific diagnostic methods are mandatory.

- Tuberculin Test (Skin Allergy Test): This is the most basic and common diagnostic method used in the field. A small amount of tuberculin antigen is injected intradermally (usually in the neck region). After 72 hours, the thickness of the skin fold at the injection site is measured. If the skin fold swells beyond a certain threshold, the animal is considered to have a positive reaction.

- Laboratory Diagnosis: More modern methods include the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to detect bacterial DNA from clinical samples, or bacterial culture for isolation. However, culturing M. bovis is very slow and requires specialized laboratories.

Prevention and Control Measures

The fundamental and mandatory principle in controlling Bovine Tuberculosis is no treatment. Any cow diagnosed as positive for the disease must be immediately culled and disposed of to eliminate the source of infection, protecting the health of the herd and the community.

- “Test and Slaughter” Surveillance Program: This is the core strategy. Veterinary authorities should organize regular testing of the entire cattle population in a region (every 6 or 12 months) using the Tuberculin test. All positive reactors must be subject to compulsory slaughter or destruction.

- Strict Quarantine: Newly purchased cattle must be quarantined and test negative for Tuberculin before being allowed to join the herd.

- Hygiene and Biosecurity: Regularly clean and disinfect barns to reduce environmental contamination.

- Food Safety: Milk must be pasteurized or sterilized before being supplied to consumers or fed to calves to kill tubercle bacilli.

Bovine Tuberculosis is more a serious public health issue than a simple economic problem for a single farm. The risk of transmission to humans through milk and air mandates disease control at a national level, not just the responsibility of individual farmers. The “Test and Slaughter” strategy, despite its immediate economic cost, is the only mandatory and effective measure to protect public health. Because the disease spreads silently and can exist in a herd for a long time before being detected, control efforts cannot succeed if they rely solely on the efforts of individual farms. A farm that does not test can become a reservoir of infection, spreading the disease to neighboring farms through trade and shared grazing. Therefore, a synchronized national surveillance and control program, led by government agencies with reasonable compensation policies for culled animals, is a prerequisite for eradicating this disease.

5. Other Important Infectious Diseases

In addition to the diseases analyzed in detail, cattle herds can be threatened by several other dangerous infectious diseases.

Anthrax

- Cause: Caused by the bacterium Bacillus anthracis, which can form spores and survive in the soil for decades.

- Symptoms: The disease is often peracute, with cattle dying very suddenly without premonitory signs. A characteristic feature is dark, non-clotting blood oozing from natural orifices (nose, mouth, anus, vulva). A typical post-mortem finding (if an autopsy is permitted) is an enlarged, soft, “blackberry jam” spleen.

- Prevention: Annual vaccination of the entire herd in areas with a history of the disease or identified as high-risk zones.

- Warning: This is an extremely dangerous disease that can be transmitted to humans and is often fatal. Never perform an autopsy on or move the carcass of a cow suspected of dying from anthrax. Immediately notify veterinary authorities for safe disposal procedures.

Bovine Viral Diarrhea (BVD)

- Cause: Caused by a Pestivirus from the Flaviridae family.

- Symptoms: The disease has diverse manifestations, from subclinical to acute forms. Key symptoms include diarrhea, oral ulcers, immunosuppression (making cattle susceptible to other diseases), and especially severe reproductive disorders such as abortion, stillbirth, congenital defects in calves, or the birth of persistently infected (PI) calves, which are the main source of infection in the herd.

Brucellosis (Contagious Abortion)

- Cause: Caused by the bacterium Brucella abortus.

- Symptoms: The most typical symptom is “abortion storms” in cattle, usually occurring in the last trimester of pregnancy. The disease can also cause arthritis and orchitis in bulls.

- Prevention: The main prevention method is vaccinating female calves between 4-8 months of age. Implement a program of regular serological testing and culling of positive animals.

- Warning: This is also a dangerous zoonotic disease.

Part III: Management and Control of Parasitic Diseases

1. Fasciolosis (Liver Fluke Disease)

Fasciolosis is one of the most common and economically devastating parasitic diseases in cattle farming in Vietnam, especially in wet grazing areas.

Cause and Life Cycle

The disease is caused by two species of trematodes from the genus Fasciola: Fasciola gigantica and Fasciola hepatica. They primarily parasitize the bile ducts and gallbladder of the liver.

The life cycle of the liver fluke is complex and requires an intermediate host, which are freshwater snails, mainly from the Lymnaeidae family. The cycle is as follows: Adult flukes in the cow’s liver lay eggs, which travel with the bile to the intestines and are passed out in the feces. In a water environment, the eggs hatch into miracidia. These larvae must find and penetrate a suitable snail to develop through several stages, eventually becoming cercariae and leaving the snail. The cercariae then swim in the water or attach to aquatic plants (like water spinach, water mimosa, or riverside grasses) and encyst, forming metacercariae. Cattle become infected by ingesting grass or drinking water containing these cysts.

Harmful Effects

Fasciolosis typically presents as a chronic disease, causing silent but persistent economic losses. The flukes in the liver cause tissue damage, hepatitis, fibrosis, and bile duct obstruction. They feed on blood and secrete toxins, leading to serious consequences:

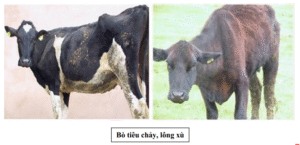

- Cattle become thin, have stunted growth, lose weight, and have a rough, easily shed coat.

- Anemia, resulting in pale mucous membranes of the eyes and mouth.

- Digestive disorders, such as persistent diarrhea alternating with constipation.

- Edema in dependent areas like under the jaw (“bottle jaw”), brisket, and chest.

- Significant productivity loss: milk yield can decrease by 15% to 50%, and fertility is reduced with delayed estrus.

In young calves, a massive, simultaneous ingestion of metacercariae can lead to an acute form of the disease, causing severe hemorrhagic hepatitis, intense abdominal pain, and rapid death due to dehydration and exhaustion.

Prevention Measures

An effective prevention strategy must target multiple links in the fluke’s life cycle simultaneously.

- Routine Deworming of the Entire Herd: This is the core and most important measure to reduce the number of adult flukes in the cattle, thereby reducing the number of eggs shed into the environment. Deworming should be done twice a year, ideally at the beginning and end of the rainy season (e.g., April and August), when snail populations are most active.

- Pasture Management:

- Manure Management: Collect and treat manure using composting. The high temperatures during composting will effectively kill the fluke eggs.

- Control of Intermediate Hosts (Snails): Improve pastures, clear bushes, and maintain drainage to dry out snail habitats. In ponds and marshy areas, molluscicides like copper sulfate ($CuSO_4$) can be used.

- Control of Infection Sources: Limit grazing in marshy, wet, or flooded areas. When cutting grass for feed, avoid cutting grass that grows near or in water.

Treatment Methods

Treatment of fasciolosis relies on the use of specific anthelmintics.

- Medication: Several active ingredients are highly effective against adult and immature liver flukes. Common drugs include Triclabendazole (effective against both young and adult flukes), Nitroxynil, Closantel, Clorsulon, and Albendazole (requires a higher dose than for regular deworming).

- Supportive Therapy: After deworming, it is necessary to combine treatment with tonics, vitamins (especially those that aid in blood regeneration), liver detoxifiers, and an enhanced diet to help the cattle quickly regain health and productivity.

Fasciolosis is a “silent enemy.” It doesn’t cause mass deaths like acute infectious diseases but erodes farm profitability slowly and inconspicuously. Farmers often overlook non-specific symptoms like thinness and poor growth, focusing only on acute illnesses. This leads to complacency and a failure to deworm regularly, allowing infection rates in the herd to rise and pastures to become heavily contaminated with eggs. Over time, the entire herd’s productivity (weight gain, milk yield, fertility) will severely decline. Therefore, establishing and strictly adhering to a routine deworming schedule should be considered a profitable investment, not a cost.

2. Hemoparasitic Diseases (Bloodborne Parasites)

This is a group of diseases caused by protozoa that parasitize inside or on the surface of red blood cells, causing anemia and high fever, transmitted mainly by blood-sucking insects.

Cause and Epidemiology

The main causative agents in cattle include:

- Babesia spp.: Causes Babesiosis, characterized by massive destruction of red blood cells.

- Anaplasma spp.: Causes Anaplasmosis, parasitizing the periphery of red blood cells.

- Trypanosoma evansi: Causes Trypanosomiasis (or Surra), living freely in the blood plasma.

The diseases are transmitted mainly through intermediate vectors like ticks, horseflies, and stable flies, which transmit the pathogens from infected to healthy animals while feeding. Therefore, the diseases often occur seasonally, peaking in hot, humid months that favor insect proliferation.

Clinical Signs

Although caused by different agents, hemoparasitic diseases often share some basic symptoms:

- High and Recurrent Fever: Cattle experience high fever ($40-41^\circ C$), which can be sustained or occur in recurrent waves.

- Severe Anemia: This is the core symptom. Due to the destruction of red blood cells or the parasites consuming their nutrients, the animal becomes severely anemic. This is visible as pale, whitish mucous membranes of the eyes, mouth, and vulva. In some cases (especially with Babesia), massive hemolysis releases hemoglobin, causing jaundice.

- Hemoglobinuria (Red Water): This is a very characteristic sign of Babesiosis. As hemoglobin is excreted in the urine, it turns a dark red, coffee, or cola color.

- Other Symptoms: Cattle become weak, emaciated, lose their appetite, and have reduced milk production. Some cases may show neurological signs like circling, tremors, convulsions, or subcutaneous edema in the brisket, dewlap, and legs.

Prevention Measures

Since the diseases are vector-borne, the most effective prevention measures focus on breaking this transmission route.

- Vector Control: This is the top priority. Regularly apply acaricides/insecticides to cattle and the entire barn and pasture area to kill ticks, flies, and mites.

- Environmental Sanitation: Keep barns clean and dry. Clear bushes, maintain drainage, and fill in puddles to destroy insect breeding and hiding places.

- Surveillance and Prophylaxis: In endemic areas, conduct regular blood tests (every 6 months) for early detection and timely treatment of cases, preventing them from becoming sources of infection. Some specific drugs (like Azidin, Trypanocides) can be used for prophylactic injections once or twice a year for the whole herd.

Treatment Methods

Treatment should be started early for high efficacy.

- Specific Drugs: Use specific drugs to kill the parasites in the blood. Common and effective active ingredients include Diminazene aceturate (found in products like Azidin, Berenil) and trypanocidal drugs.

- Supportive Therapy: This is a critical part of saving the animal.

- Blood Transfusion: In cases of severe anemia (whitish mucous membranes), a blood transfusion from a healthy donor cow is a necessary emergency measure.

- Support and Recovery: Administer supportive drugs, vitamins (especially Vitamin B12 and iron to aid red blood cell regeneration), and fluid therapy (glucose, saline) to rehydrate and provide energy.

The link between hemoparasitic diseases and their vectors is inseparable. The life cycles of these protozoa depend entirely on blood-sucking insects for transmission from one animal to another. Therefore, any effort to treat individual sick cattle will be futile and costly if not accompanied by a strict and sustainable vector control program. Killing ticks and flies should not be seen as a supportive measure, but as the fundamental, strategic method of prevention.

3. Gastrointestinal Helminthiasis

Cause

This is caused by a diverse group of nematodes (roundworms like ascarids, hookworms, whipworms) and cestodes (tapeworms) that parasitize the various compartments of the stomach and intestines. Cattle get infected by ingesting feed, grass, or water contaminated with worm eggs or larvae.

Calves aged 1-3 months are particularly susceptible to the calf roundworm (Toxocara vitulorum), which can cause high mortality.

Harmful Effects

Helminths cause harm through several mechanisms:

- Nutrient Competition: They absorb a large portion of nutrients from the host’s food, leading to emaciation, stunted growth, a rough and dry coat.

- Causing Damage and Digestive Disorders: Worms attach to the intestinal mucosa, causing inflammation and damage, which reduces nutrient absorption. This results in persistent diarrhea, with foul-smelling, loose feces, sometimes containing blood, mucus, or even visible worms.

- Causing Anemia: Some worm species (like hookworms) feed directly on blood from the intestinal wall, leading to chronic anemia.

- Immunosuppression: Chronic helminth infection weakens the body’s overall resistance, creating conditions for other infectious diseases to emerge.

Prevention and Treatment Measures

The strategy for managing helminths is based on breaking their life cycle and reducing the parasite load.

- Routine Deworming: This is the most core and effective measure.

- For Calves: The first roundworm deworming should be done when they are about 1 to 1.5 months old, as this is their most susceptible period.

- For the Entire Herd (heifers and adult cows): Deworm regularly twice a year (every 6 months), usually at the beginning and end of the rainy season.

- Use of Anthelmintics: Choose broad-spectrum dewormers effective against various types of worms. Common active ingredients include Ivermectin, Fenbendazole, Albendazole, Mebendazole, and Levamisole. Rotating between different drug classes can help slow the development of anthelmintic resistance.

- Environmental Sanitation: Keep barns dry and clean. Collect and compost manure using methods that generate high temperatures to kill worm eggs, preventing their spread into the environment.

Part IV: Specific Health Challenges in High-Producing Dairy Cows

High-producing dairy cows, due to genetic and physiological pressure to produce large volumes of milk, face unique health challenges, mainly related to the udder, metabolic disorders, and obstetric problems.

1. Mastitis: A Comprehensive Analysis

Mastitis, an inflammation of the mammary gland, is recognized as the single most costly disease in the global dairy industry. Losses are not just from medication costs but also from reduced milk yield (10-30%), lower milk quality (increased somatic cell count, making milk substandard), and the risk of premature culling of genetically valuable cows.

Cause

The direct cause of mastitis is the invasion and multiplication of microorganisms, primarily bacteria, into the udder through the teat canal. These pathogens can be classified into two main groups based on their source and transmission mechanism:

- Contagious Pathogens: This group spreads mainly from infected cows to healthy ones during the milking process, via the milker’s hands, shared udder cloths, or milking machine components. The most typical and dangerous pathogens in this group are Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus agalactiae.

- Environmental Pathogens: This group is present in the cow’s environment, such as in manure, bedding, soil, and dirty water. They invade the udder between milkings, especially when a cow lies down on contaminated bedding. The most common agents are Escherichia coli (E. coli), Klebsiella spp., and Streptococcus uberis.

Besides bacterial agents, numerous risk factors contribute to an increased likelihood of the disease:

- Housing Environment: Dirty, damp, and poorly ventilated barns are ideal environments for environmental bacteria to thrive.

- Milking Management: Poor udder hygiene before and after milking, improper milking techniques (causing teat injury), and dirty milking equipment are leading causes.

- Individual Cow Factors: Poor udder conformation (large, pendulous udders), old age, early and late stages of lactation (when udder immunity is weaker), and poor overall body condition.

- Nutrition: An imbalanced diet, especially a deficiency in antioxidants like Vitamin E and Selenium, can weaken the mammary gland’s defense mechanisms.

Classification and Symptoms

Mastitis is divided into two main forms:

- Clinical Mastitis: This is the form with visible symptoms.

- Systemic Signs: The cow may have a high fever, be lethargic, and off-feed.

- Local Signs (Udder): One or more quarters are swollen, hot, red, and painful to the touch.

- Milk Changes: The milk appears visibly abnormal: watery, with flakes, clots (like yogurt), pus, or blood, and may have a foul smell.

- Subclinical Mastitis: This is the more common and economically damaging form. In this form, the udder and milk appear completely normal. However, an infection exists within the mammary gland, leading to reduced milk production and, most importantly, a sharp increase in the somatic cell count (SCC), which mainly consists of white blood cells.

Diagnosis

- Clinical Mastitis: Easily diagnosed by observing the signs of swelling, heat, redness, and pain in the udder and changes in the milk.

- Subclinical Mastitis: Requires cow-side tests for detection. The most common and effective method is the California Mastitis Test (CMT). This test is based on the reaction between a reagent and DNA from somatic cells in the milk. If the SCC is high (an indicator of infection), the milk-reagent mixture will form a gel of varying consistency, allowing for a rough estimation of the severity of inflammation.

Integrated Prevention Strategy

Effective mastitis prevention requires a multi-faceted control program, often summarized in the “Five-Point Plan”:

- Implement Strict Hygienic Milking Procedures: This includes cleaning the udder before milking, fore-stripping to check for abnormalities, complete milking, and most importantly, post-milking teat dipping of all teats in a dedicated disinfectant immediately after every milking to kill bacteria and create a protective barrier.

- Prompt and Proper Treatment of All Clinical Cases: Sick cows should be isolated (milked last) and treated immediately to reduce pain, limit damage to the gland, and prevent them from becoming a source of infection for the herd.

- Implement Dry Cow Therapy: On the last day of lactation before the dry period, infuse a long-acting antibiotic into all four quarters. This measure aims to cure existing subclinical infections and prevent new infections that may occur during the dry period, a high-risk time for mastitis.

- Cull Chronically Infected Cows: Cows with recurrent mastitis that does not respond to treatment are a constant source of S. aureus for the herd. Keeping them is more costly than their production value, so they should be considered for culling.

- Maintain a Clean, Dry, and Comfortable Living Environment: Pay special attention to the cow’s lying area. Bedding must be dry, clean, and plentiful to minimize the teats’ exposure to environmental bacteria.

Treatment Methods

- For Clinical Mastitis:

- Empty the Udder: Frequently strip out all milk and inflammatory products from the affected quarter (3-6 times a day) to remove bacteria and toxins.

- Intramammary Infusion: Use specialized antibiotic tubes to infuse medication directly into the inflamed quarter after each milking.

- Systemic Treatment: In severe cases where the cow shows fever and systemic signs, systemic antibiotics (intramuscular injection) combined with anti-inflammatory drugs and antipyretics are necessary to control the infection and reduce pain.

- For Subclinical Mastitis: Treatment during lactation is often not highly effective and leads to milk discard (due to antibiotic residues). Therefore, the most effective treatment for this form is the application of dry cow therapy.

Classifying pathogens into contagious and environmental groups is key to developing an effective and targeted prevention strategy. If culture results from farm milk samples show that the primary agent is S. aureus (contagious), then the focus of improvement must be on milking procedures, equipment hygiene, and strict adherence to post-milking teat dipping. Conversely, if the main problem is E. coli (environmental), the top priority must be improving barn hygiene and keeping the cows clean and dry. A generic prevention strategy not based on identifying the root cause is unlikely to be effective. Furthermore, the dry period should not be seen as a “rest” period but as the “golden” opportunity for mastitis control. It is the best chance to cure subclinical infections with long-acting antibiotics without worrying about residues in marketable milk. Skipping dry cow therapy means missing the most effective and economical opportunity to control the disease, allowing cows to start a new lactation with a healthy udder.

2. Metabolic Disorders in the Transition Period

The transition period, encompassing 3 weeks before and 3 weeks after calving, is the most stressful and challenging phase in a dairy cow’s production cycle. Sudden changes in hormones, physiology, and nutritional demands make cows highly susceptible to metabolic disorders, which are often interrelated.

Milk Fever (Hypocalcemia)

- Cause: The disease occurs due to a sudden and drastic drop in blood calcium levels immediately after calving. The demand for calcium to produce large amounts of colostrum is extremely high, while the cow’s mechanisms for mobilizing calcium from bones and increasing intestinal absorption have not yet adapted, leading to an acute deficiency. The disease is common in high-producing dairy cows, especially from the third lactation onwards, as their ability to mobilize calcium begins to decline.

- Symptoms: The disease progresses through three distinct stages:

- Stage 1 (Excitement): The cow appears restless, with muscle tremors, and walks with an uncoordinated, staggering gait.

- Stage 2 (Sternal Recumbency): The cow is unable to stand, lies down, and often tucks her head into her flank. Her body temperature drops (despite the name “milk fever”), extremities are cold, and muzzle is dry. Smooth muscle paralysis leads to cessation of rumination, ruminal bloat, and an inability to defecate or urinate.

- Stage 3 (Coma): The cow loses consciousness, lies on her side, becomes severely bloated, and can die within hours if not treated promptly.

- Prevention: Effective prevention depends entirely on nutritional management during the dry period.

- Limit Pre-calving Calcium: Feed a low-calcium diet during the final weeks of the dry period. This “primes” the calcium-regulating hormonal system (parathyroid hormone and Vitamin D), making it more responsive and ready to mobilize large amounts of calcium right after calving.

- Use an Anionic Diet (Negative DCAD): Feed a diet with a negative Dietary Cation-Anion Difference (DCAD) for 2-3 weeks pre-calving. This diet slightly lowers blood pH, which enhances calcium absorption from the gut and mobilization from bone.

- Supplement with Vitamin D3: Injecting Vitamin D3 about 5-7 days before the expected calving date can help increase calcium absorption.

- Treatment: This is a veterinary emergency. The only effective treatment is the slow intravenous infusion of a calcium solution (usually calcium gluconate). Rapid infusion can cause cardiac shock and arrest. After the cow is able to stand, supplemental calcium should be given orally or subcutaneously to maintain blood calcium levels.

Ketosis

- Cause: The disease is a direct consequence of a severe negative energy balance after calving. The energy demand (for glucose) to produce a huge volume of milk far exceeds the cow’s ability to consume energy from feed. To compensate, the body mobilizes and breaks down large amounts of fat reserves. This process produces byproducts called ketone bodies (acetone, acetoacetate, $\beta$-hydroxybutyrate). When ketone production exceeds the body’s ability to use them, they accumulate in the blood, causing toxicity and leading to the disease.

- Symptoms: The cow shows a marked decrease in appetite, especially for concentrates, and may only nibble at forage. Milk production drops suddenly, and the cow rapidly loses weight and body condition. A characteristic sign is the smell of acetone (a sweet, nail polish-like odor) on the cow’s breath, in her milk, and urine. Some cases may exhibit neurological signs such as abnormal licking of objects, aimless walking, or agitation.

- Diagnosis: In addition to clinical signs, the disease can be quickly and accurately diagnosed cow-side using dipsticks to detect ketones in urine or milk.

- Prevention:

- Body Condition Management: Avoid cows becoming overweight (Body Condition Score $\geq 4/5$) at the end of the dry period. Fat cows tend to have a greater drop in appetite after calving and mobilize more fat, increasing their risk of ketosis.

- Maximize Feed Intake: This is the key factor. Provide palatable, high-quality feed and ensure cows have constant access to it. After calving, gradually increase the amount of concentrate in the ration to meet rising energy demands.

- Supplement Glucose Precursors: Adding substances like propylene glycol or calcium propionate to the diet can provide a direct energy source and reduce the burden on the liver’s gluconeogenesis process.

- Treatment:

- Provide Quick Energy: Intravenous infusion of a glucose solution is the most immediate and effective intervention.

- Provide Glucose Precursors: Drench the cow with propylene glycol daily for several days to provide a sustained energy source.

- Use Hormones: Injecting a glucocorticoid (e.g., Dexamethasone) stimulates the liver to produce glucose from other sources, helping to raise blood sugar levels.

- Support Liver Function: Supplement with B vitamins, especially Vitamin B12, to support energy metabolism in the liver.

Metabolic diseases in the transition period are not isolated events but a closely linked pathological domino effect. A drop in feed intake before calving leads to a negative energy balance, resulting in Ketosis. The spike in calcium demand after calving causes Milk Fever. Hypocalcemia itself reduces smooth muscle contractility throughout the body. When rumen motility decreases, the risk of a Displaced Abomasum increases. When uterine contractility is reduced, the risk of Retained Placenta and Metritis also rises. Both Ketosis and Milk Fever suppress the immune system, paving the way for Mastitis. Therefore, the success or failure of an entire lactation is determined in the 6-week window around calving. Treating individual diseases is only a temporary fix. The most sustainable and effective strategy is to prevent this complex disease syndrome through a comprehensive transition period management program focused on maximizing feed intake, providing a scientifically formulated diet, and creating a comfortable, stress-free environment for the cow.

3. Digestive and Obstetric Disorders

Ruminal Bloat (Tympany)

-

- Cause: This occurs due to the rapid and excessive accumulation of gas in the rumen that the animal cannot eructate (belch) quickly enough. The most common cause is the consumption of large quantities of highly fermentable feed such as lush young pasture (especially legumes), watery leafy greens, or spoiled, moldy feed.

- Symptoms: The condition progresses very rapidly. The cow’s left paralumbar fossa (flank) becomes visibly distended, tight like a drum. The cow shows signs of pain, is restless, and constantly gets up and down. The distended rumen presses heavily on the diaphragm and lungs, causing severe respiratory distress, with the cow breathing through its mouth with its tongue out. If not treated as an emergency, the cow can die quickly from asphyxiation and heart failure.

- Emergency Treatment:

- Mechanical Measures: Immediately position the cow to stand with her front end elevated to reduce pressure on the diaphragm. Pull the cow’s tongue out of her mouth in rhythm with her breathing to stimulate the belching reflex. Vigorously massage the left flank area with straw or your hands to stimulate rumen motility.

- Chemical Measures: Drench the cow with substances that can break down foam or inhibit gas-producing fermentation. Effective folk remedies include giving vegetable oil, garlic-infused alcohol, pickled brine, or beer.

- Surgical Intervention: In severe, rapidly progressing cases where the cow is at risk of suffocation, the last resort is to use a specialized instrument called a trocar to puncture the abdominal wall and rumen in the left flank area. The gas must be released slowly to avoid a sudden drop in pressure, which can cause shock and cardiovascular collapse.

Displaced Abomasum (DA)

- Cause: This is a condition where the abomasum (the true stomach) fills with gas and moves from its normal position on the floor of the abdomen, floating upwards and usually becoming trapped on the left side, between the rumen and the abdominal wall. The main risk factor is reduced appetite and rumen fill after calving, which creates an empty space in the abdomen allowing the abomasum to move. The condition is closely linked to other metabolic disorders like Milk Fever and Ketosis, which decrease gastrointestinal motility.

- Symptoms: The cow shows a gradual decrease in appetite, reduced milk yield, and produces little manure. The definitive diagnostic sign is hearing a high-pitched, metallic “pinging” sound when percussing (flicking) the left flank while simultaneously listening with a stethoscope.

- Treatment: This condition requires veterinary intervention. Treatment methods include rolling the cow in a specific sequence to allow the abomasum to return to its normal position, or surgery to suture the abomasum to the abdominal wall.

Retained Placenta

- Cause: Normally, the fetal membranes are completely expelled within 12 hours after calving. A retained placenta occurs when the membranes fail to detach and are held in the uterus for more than 12-24 hours. Risk factors include dystocia (difficult birth), premature birth, twinning, infectious diseases causing placentitis (like Brucellosis), and especially hypocalcemia (Milk Fever), which reduces uterine contractility. Nutritional deficiencies such as Selenium and Vitamin E are also thought to be involved.

- Symptoms: The most obvious sign is a portion of brownish, dirty membranes hanging from the vulva. A foul-smelling discharge may drain from the vulva. The cow may show systemic signs like a mild fever, reduced appetite, and decreased milk production.

- Management:

- Never manually pull out the placenta forcefully if it has not fully detached. This can cause severe damage to the uterine lining, leading to hemorrhage and severe infection.

- Use hormones like Oxytocin or Prostaglandin ($PGF_{2\alpha}$) to stimulate stronger uterine contractions to help expel the placenta naturally.

- Administer antibiotics (systemic injection or intrauterine boluses) to control bacterial growth and prevent subsequent metritis.

Metritis/Endometritis

- Cause: This is often a direct consequence of obstetric problems like a retained placenta, dystocia, or unhygienic assistance during calving. Bacteria from the external environment enter the uterus, which is in a vulnerable and compromised state post-calving, leading to infection.

- Symptoms: The characteristic sign is an abnormal discharge from the vulva. This can be a watery, reddish-brown, foul-smelling fluid (acute metritis) or a thick, whitish-gray pus (pyometra). The cow may have a fever, be off-feed, and have reduced milk yield. Uterine infections severely affect fertility in subsequent breeding cycles.

- Treatment:

- Uterine Lavage: Use a soft catheter to infuse a mild antiseptic solution (like saline, 1% Lugol’s iodine, or 1‰ potassium permanganate) deep into the uterus to flush out inflammatory fluid and pus.

- Hormone Use: Inject Prostaglandin ($PGF_{2\alpha}$) to cause luteolysis (if a corpus luteum is present), which helps open the cervix and enhances uterine contractions to expel the pus.

- Antibiotic Use: Combine systemic antibiotic injections with the placement of specialized antibiotic boluses directly into the uterus to kill bacteria at the site of infection.

Part V: Developing a Comprehensive Veterinary Health Program

1. Integrated Preventive Health Schedule

To manage herd health proactively and effectively, establishing and adhering to a clear, scientific preventive health schedule is paramount. Based on the information analyzed, an integrated schedule including vaccinations and parasite control is recommended as follows.

| Vaccine Type | Target Animal | First Vaccination | Booster Schedule | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foot-and-Mouth Disease (FMD) | Calves | 2-4 months of age | Every 6 months | A polyvalent vaccine containing locally relevant serotypes (O, A, Asia1) should be used. |

| Hemorrhagic Septicemia | Calves | 3-4 months of age | Every 6 months (usually before the rainy season) | Very important in regions with sudden climate changes, which are a trigger for the disease. |

| Lumpy Skin Disease (LSD) | Calves | From 2 months of age | Every 12 months | Must be combined with strict insect control measures (flies, mosquitoes, ticks). |

| Anthrax | Entire herd | As per local veterinary recommendation | Annually | Only vaccinate in areas with a history of the disease or designated as high-risk. |

| Brucellosis | Female calves | 4-8 months of age | Once only | Only vaccinate female calves for prevention; do not vaccinate bulls or adult cows. |

| Parasite Type | Target Animal | Timing | Recommended Drugs (Active Ingredient) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roundworms (Ascarids) | Calves | 1st time: 1-1.5 months of age | Piperazine, Levamisole, Ivermectin | This is the most susceptible period for calves. A repeat dose after 4-6 days may be necessary. |

| Gastrointestinal Helminths (General) | Entire herd | Every 6 months | Ivermectin, Fenbendazole, Albendazole | Rotate between drug classes with different mechanisms of action to slow the development of anthelmintic resistance. |

| Liver Fluke | Entire herd | Every 6 months (usually at the start and end of the rainy season, e.g., April & August) | Triclabendazole, Nitroxynil, Closantel | Prevention efficacy heavily depends on combining treatment with snail control and pasture management. |

2. Practical Recommendations and Conclusion

For a veterinary health program to be truly effective, merely following a schedule is not enough. Farmers and farm managers must emphasize record-keeping. All health activities (vaccination date, vaccine type, batch number, treatment date, drug type, dosage), production events (breeding date, calving date, daily milk yield), and any unusual changes in the herd should be meticulously and systematically recorded. This data is an invaluable asset, providing the basis for analyzing the effectiveness of management practices, detecting disease trends early, and making evidence-based intervention decisions, rather than relying solely on intuition.

In conclusion, managing herd health is a dynamic, continuous process that requires an integrated approach, not a series of isolated actions. Success depends not on a single factor but on the tight and harmonious integration of three main pillars: (1) Proactive Prevention through strict adherence to vaccination schedules and biosecurity principles; (2) Optimal Management and Care, especially providing scientifically-based nutrition for each physiological stage and maintaining a clean, comfortable living environment; and (3) The Ability for Early Detection and Intervention at the first sign of illness. In modern livestock farming, investing in prevention always yields a higher and more sustainable economic return than the cost of remedying the severe consequences of disease outbreaks.

References

1) COMMON DISEASES IN DAIRY CATTLE (JICA)

A document summarizing common diseases and their management, including: ruminal bloat, heatstroke, poisoning, traumatic pericarditis, bloodborne parasites (Trypanosoma, Anaplasma, Babesia/Theileria), liver fluke, and diarrhea syndrome & roundworms in calves. The treatment section specifies objectives, drugs/supportive measures (rumen tubing, electrolytes, antipyretics, cardiac stimulants, fluid therapy…).

Download document: JICA – PDF

2) NEMA1 – Environmental Treatment Product (Reference solution for cattle housing)

Product documentation presenting a solution to reduce odors (NH3, H2S, volatile acids), support beneficial microbial growth, and naturally repel flies; for direct application in cattle/dairy farming areas to improve environmental conditions, helping to mitigate environmental risk factors that exacerbate disease.

See details: NEMA1 – JV Smart Future